The Wayward Wind by Peter Murphy

Photos by Mick Quinn

Hot Press

4 June 2003

(This is part 1. Here is part 2.)

From “Outspan” to Glen Hansard, from Grafton Street to Hollywood – and onwards to Lisdoonvarna 2003. A portrait of The Frames as a most unusual band. Part one of a two-part special feature.

From “Outspan” to Glen Hansard, from Grafton Street to Hollywood – and onwards to Lisdoonvarna 2003. A portrait of The Frames as a most unusual band. Part one of a two-part special feature.

Let’s just say there was a wayward wind abroad in Ireland towards the late ’80s; freak weather that caused a whole generation of popkids to turn off the radio and look to their elders for inspiration in a time historians have written off as being overrun by chart tarts. Born too late for punk, many of these youngsters inherited values of musicianship and live performance through the rites of hard rock passage, the folk ballad elements in Lizzy and Led Zep. In effect, they went from Back In Black to Blood On The Tracks without batting an eyelid.

What came out the other end was the raggle-taggle mafia, a loose aggregation of strolling players that, in the absence of cosmopolitan critical kudos, started their own rustic block party. For years that period has been dismissed by scribes like George Byrne and singers such as Cathal Coughlan – architect of those infamous Raggle-Taggle Nein Danke t-shirts – as an embarrassment. And true enough it produced relatively few recorded artefacts of any enduring interest. But what it did was provide a petri dish for a germ culture that is now beginning to yield its own antidotes to this age, one easily as ephemeral as the ’80s.

Raggle-taggle was a rural ideal that took root in the capital city, mainly centred around the busking community on Grafton Street: The Benzini Brothers (soon to morph into Hothouse Flowers), the embryonic Frames, Kila, The Mary Janes, Mark Dignam, Nina Hynes, plus affiliates like The Black Velvet Band, The Dixons, Interference, Galway’s The Swinging Swine, Wicklow’s The Prayer Boat, and after the fact, The Big Geraniums. Added to this was the presence of high pedigree blow-ins such as Maria McKee carrying roots rock seedlings from a west coast paisley underground also inhabited by The Long Ryders, Green On Red et al.

As movements go, it was hardly as earth shaking as Madchester or punk (although it certainly borrowed punk’s DIY ethos and an anti-authoritarianism born of busking, albeit cross-bred with nouveau-hippy positivism), but it was significant enough to make for major features in style bibles like The Face and the NME.

And if it was a wayward wind, it had had been gathering force for a few years. From the ’70s and early ’80s, Horslips, Moving Hearts and Rory Gallagher tours instilled in young Irish gig goers a regard for virtuosity and song-craft not necessarily found in London or New York. Then came a series of mini-renaissances from rock ‘n’ roll’s high priests: the biblical apparition of Dylan at Slane in ’84; Van’s appearance at Self Aid heralding No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, his best album in ages; Leonard Cohen’s comeback album Various Positions and the smoky romanticism of ‘Dance Me To The End Of Love’ which brought him video airplay on MT-USA. See also: T-Bone Burnett, Elvis Costello’s King Of America, David Byrne’s forays into Americana, REM getting garlanded as successors to The Byrds and The Band and U2’s increasing facility with folk, blues, Woody Guthrie and the literature of the American south. Soon Patti Smith would emerge from retirement, and while Dream Of Life was no Horses, her presence would at least jolt memories of the great Gnostic poetic championships. Neil Young’s blazing return to form was still a year or two away, but the 1985 Old Ways album excavated his country roots and momentarily cleared the fog of his last days on Geffen.

That album contained a wood-stained version of – you guessed it – ‘The Wayward Wind’, one of the totems that convinced Mike Scott to forsake the big music of A Pagan Place and This Is The Sea, and in tandem with Anthony Thistlethwaite and Dubliner Steve Wickham, remake The Waterboys as a spontaneous combuskable live unit á la Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance or Bob’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Scott was also under the influence of Scotland’s We Free Kings, a rowdy hybrid of The Incredible String Band, The Clash, the French Symbolists and Green radicalism, fronted by the gravel-voiced urchin Joe Kingman.

That album contained a wood-stained version of – you guessed it – ‘The Wayward Wind’, one of the totems that convinced Mike Scott to forsake the big music of A Pagan Place and This Is The Sea, and in tandem with Anthony Thistlethwaite and Dubliner Steve Wickham, remake The Waterboys as a spontaneous combuskable live unit á la Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance or Bob’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Scott was also under the influence of Scotland’s We Free Kings, a rowdy hybrid of The Incredible String Band, The Clash, the French Symbolists and Green radicalism, fronted by the gravel-voiced urchin Joe Kingman.

The Waterboys’ incendiary shows in Ireland throughout 1986-89 put torch to tinder, and pretty soon you could feel a griot riot going on, a griot riot of our own. Everybody’s hair grew three feet overnight. The dress code was Romany refugee chic ten years before the fact – ripped 501s, Dock Martins, paisley shirts and thrift shop scarves picked up in shops like Se/Si. The dubious dignity of menial labour was eschewed in favour of slacking on Grafton Street, browsing through bootlegs on O’Connell Bridge, prowling around the George’s Street Arcade, living on leftover sandwiches from Marx Bros, drinking in Grogan’s, a small town pageant bearing the scent of patchouli, doobies and Guinness-sweat. Some days, if you breathe in deep enough, you can still catch a sough, a sigh, a whiff of that wayward wind.

Or maybe it’s the drugs.

Now it’s 15 years later. We’re only a few minutes into the taping of the Today FM documentary Revelations – The Story Of The Frames in February 2003 when this writer gets a hit of deja voodoo off that long forgotten breeze. Frames frontman Glen Hansard and fiddle player Colm Mac An Iomaire are in for what will turn out to be a marathon interview, the former still buzzing from the 100,000 strong anti-war rally that took place in the city centre throughout the afternoon. At that demonstration, Hansard had spotted his buds Mundy and Damien Rice in the mob of peaceniks, and after exchanging nods and gestures, took to the stage to busk a few impromptu tunes. In the midst of the madness, the singer spotted a bedraggled figure pushing his way through the crowd on crutches, trying to scale the barrier to get onstage. It was Shane MacGowan, demanding if Glen knew the chords to ‘And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda’. They played it, but the rally had run into extra time and the law moved in to clear the musicians from the stage. To his amusement, Glen saw that the Guard in charge of turfing them off was the same one who used to bust him for busking on Grafton Street 15 years before. Both had risen in the ranks somewhat, but their opposing roles remained unchanged.

“I think most of the things in our career that have been positive came from busking actually,” Glen reflects, coming down from the buzz of the demo. “With busking it was always, if you’ve got a horseshoe shaped crowd standing around you, then it was all about keeping them there, it was never about the money. We made more money from busking than we did in The Frames for the first eight years, but it was more a sense of getting everybody involved somehow, and I think the very early Frames gigs had that, and it never went, it just seemed to get stronger.”

Wired and tired, Hansard reminisces about these times, dredging up memories.

“When I started busking, the repertoire of songs we were playing was mostly Bob Dylan and Neil Young songs,” he says, “and I remember myself and Mic Christopher and Mark Dignam, we met up with these other two lads who were from Wexford, and they were called Acko and Swanny. We didn’t really know them but they had an amazing wild energy off them. They were singing songs we didn’t know, but we sort of joined up with them and they became another part of our group. And I remember Acko putting a Walkman to my ears, and he was like, ‘Here, check this band out, they’re amazing,’ and he played me The Waterboys and it was This Is The Sea.

“And then I remember Acko giving me the Walkman again and saying, ‘Here check this out’ and he was playing songs from Document by REM, another band I’d never heard of. So it has to be said that Acko was an incredible inspiration to us in terms of the songs we played because he seemed to be, you know, that guy in your class who knows all the cool bands, who sorta does all the research, and he’s the one who influences a whole movement when he puts his head down to it.”

In fact, this writer knew Acko as Martin Atkinson, a tall, skinny, gregarious character who’d relocated from Tallaght to Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford. I first met him on Rafter Street in August 1984, and we immediately became entangled in a heated argument about Santana’s support slot to Dylan at Slane that summer (he was pro, I felt conned). Over the next year, odd Sundays were enlivened by the arrival from Dublin of Acko’s friend Swanny, aka Vincent Swan, a guitar playing wideboy and apprentice baker. The two would practice as a duo in The Athenaeum or in the local handball alley on the prom, cranking out Billy Bragg and Smiths songs, later forming a short-lived goth-rock combo called The Eleventh Hour.

Then The Waterboys released This Is The Sea in September 1985, and it did for us what Desire did for our big brothers. Via the Steve Wickham connection, the band blew into Dublin in January of 1986 looking like a flashback to a different age, swashbuckling gypsies steeped in old-world romanticism. When the band went on tour that April, word about the new Waterboys line-up spread like an epidemic.

“This incredible new band that we had all gotten excited about, the guys were walking up and down the street while we were playing,” Glen Hansard remembers. “Getting to meet Mike Scott and Steve Wickham and Anthony Thistlethwaite was incredible because they would stop and play with us or have a chat, and it was the very first time certainly in my life where a hero was suddenly somebody who you could possibly bump into on the street.

“I remember meeting Mike Scott and asking him to take part in a gig he was organising for a charity, and he gave me his phone number, he was absolutely open, there was no sense of, ‘Hang on, I’m the rock star and you’re Johnny Public’. And I remember thinking that was an incredible template for the way to live your life – yeah, sure, do your thing, and if you’re someone’s hero then so be it, but never lift yourself above what you are, which is a human being.”

This writer saw The Waterboys on the Waterford date of that Irish tour. Within days, we all wanted to learn the mandolin or violin, like kids pretending to be Errol Flynn after the Saturday afternoon matinee. We Free Kings also did a camping tour of Ireland a few months after that, accompanied by Scott and Wickham. From spring to fall of 1986, it seemed like everybody under 30 had gone mitching.

I remember a motley troupe of musicians traipsing into Enniscorthy town that summer and setting up an encampment on the prom, friends of Acko and Swanny’s who looked like they’d blundered out of the skyline scene in ‘The Seventh Seal’. One of them was wearing an Iron Maiden t-shirt but singing Simon & Garfunkel, a useful indication of where a lot of the raggle-taggle lot were coming from. This mob turned out to be an advance party from the pool of musicians that would eventually spawn The Frames, including Mark Dignam and future Kila fiddle player Dee Armstrong.

The first time your correspondent ever heard Glen Hansard’s name was at one of the then thriving sessions in Crane’s pub in Enniscorthy. Eddie, son of proprietor Jimmy, was a schoolteacher and local musician who together with Paddy Kehoe (now a journalist with the RTE Guide) formed the backbone of those happenings. The two were friendly with the Sonny Condell/Tir Na Nog/Scullion clan, itself a kind of predecessor to the Frames nexus. Anyway, one night Eddie came in fresh from having seen Niall Toner’s band Hank Halfhead & The Rambling Turkeys. Niall Junior had just left to front The Dixons, his replacement being the 19-year-old Hansard, whom Eddie talked about with the air of a boardwalk bystander who’d just witnessed Billy The Kid pulling off some audacious gunplay exhibition in the saloon the previous night. “This kid has the fastest right hand I’ve ever seen,” he said, miming a hummingbird-like strum on his acoustic.

I saw the sight for myself on Grafton Street later that year, Glen hanging with his hippy homies, all Crazy Harry eyes and strawberry blonde ringlets, lashing out ‘Be My Enemy’ with all the other Water-bes. Before long I was introduced to him and Mic Christopher on South Anne Street, lingering on the fringes of the Coffee Inn crowd. Mic was just back from London, as was Acko, both refugees from the Hare Krishna hippy scene that trafficked back and forth from Dublin to Kilburn.

Acko had left Ireland full of Richard Bach and CSN&Y and came back talking about Bukowski and The Pixies. Again, he had Hansard’s ear. In the parlance of the day, things were getting heavy. Ex-Frames guitarist Dave Odlum remembers the point where Glen’s freewheeling busking vibe started to evolve into something more ambitious:

“We used to busk down the lane between Powerscourt and Grafton Street, there was no musical thing that brought everybody together particularly; we just ended up hanging out. Then I remember hearing that he’d been offered a publishing deal, and I was like, ‘Well, what does that mean? Does it mean he’s gonna write a book?!’ Like, we were all very naïve about the thing, and I think Glen, probably more out of necessity than anything, focused on his music a little more as a career.”

Glen recorded a demo of his own songs with members of The Blue Angels, and when his friend Marina Guinness passed the tape onto legendary Island Records talent scout Denny Cordell, he got an invite to take the train down to Carlow.

Glen: “Denny picked me up, and Marianne Faithfull was in the car with him, and it was like, ‘Hel-looow! Hey! Wow!’ (And he said) ‘We’ve been listening to your tape, we think it’s really good.’ And as we got to the house, Stewart Copeland was on a horse in the garden, and he got off and said hello and I was like: ‘Fuck! Howya man!’ Cos I’d been to see the Police in 1980 in Leixlip Castle, and I was a real fan. And we went into the house and Ronnie Wood was there. So you can imagine the situation. I was freaked out. These were like, four people sittin’ around the table, drinkin’ tea, smokin’ spliffs and listening to my demo and sorta goin’, ‘Y’know, this is really good.’ And Stewart was saying, ‘My brother Miles would really like this, I think I’ll call him.’ And I was like, ‘Aw man, this is amazin’!’”

Later that evening Cordell put Glen on the phone to Island boss Chris Blackwell. Without even trying too hard, it looked like he’d scored a deal. He signed to Island as a solo act, and armed with the advance, set about recruiting Dave Odlum, singer Noreen O’Donnell, bass player John Carney and drummer Binzer. Fiddler Colm Mac An Iomaire wandered up to the band’s Temple Lane rehearsal room from a Kila recording session downstairs in Sun and never left. Kila’s Ronan O’Snodaigh, then doubling as The Frames’ percussionist, soon departed, too much the natural bandleader to assume a subsidiary role. The Frames stabilised as a six-piece, but when the Island delegates came over to take a look at their investment, they were decidedly underwhelmed.

“Of course they hated us and thought I should sack everyone and get, like, a bunch of session musicians in,” Glen recalls. “That was the first clash we had, and that was the moment when I realised that they were wrong and I was right. They didn’t think The Frames were any good and I thought we were deadly!”

Right about now that old wayward wind conspired to blow The Frames’ boat into strange waters. Accompanying an actor friend to an audition for Alan Parker’s film of ‘The Commitments’, Glen was persuaded by the casting agent to read for the part of Outspan Foster. To his shock, he got the job. The next three months were a blur of getting up at dawn to spend all day filming, then rehearsing with the band at night. The strain soon showed on his face, much to Parker’s displeasure, and when one of The Frames’ gigs clashed with a crucial shooting date, matters came to a head.

“Alan had said to me, ‘If you need anytime off just let us know, give us a good week’s notice,’” Glen explains. “So I gave him a week’s notice and said, ‘Listen, I’ve got this gig.’ And it just happened to be the night that they booked the DART for a scene where we’re all (singing) ‘Destination Anywhere’. They had to reschedule the DART night, and he was like, ‘I can fire you from this film, I can get rid of you’, blah, blah, blah, and he put it to me, he said, ‘You’re not doing your gig.’ And I said, ‘I am.’ And he said, ‘No you’re not. You’re doing this film. You signed up to this film, and we’re only a few weeks into shooting and I will replace you.’ And I was like, ‘Well you’ll have to replace me because I’m in a band and that’s what I do, and your film is your thing, this isn’t my thing.’ And I had to lay the law with him, and me and him got… it was well heavy actually, to be honest. I think he appreciated it in the end, ’cos he said to me a year later, ‘I respect you more for what you said, but at the time I wanted to kill you.’ So the Frames gig happened and they lost whatever it was, £25,000, hiring the DART line for the night.”

With principal photography on the film completed, Glen went back to preparing for The Frames’ first album, but he wasn’t shut of his Commitments obligations just yet. Under contract to take part in the American publicity tour for the film, he reluctantly agreed to put his band on hold again. However, on that tour he did meet a pre-Sin E Jeff Buckley, who’d been hired to play guitar in ‘The Commitments’ band for premieres in LA, New York and Chicago.

“Me and him just got on so well because he was a Bob Dylan freak and a Van Morrison fan and so was I,” Glen says. “And every night we would just rattle on about Van, we were travelling through America, and when we got to Chicago I remember sitting at the soundcheck with Jeff and I started playing ‘Once I Was’ by Tim Buckley, ’cos I’d just gotten into him at the time. And Jeff was like, ‘He was my da, y’know’. And I looked at him and I was like, ‘No way. Wow. That makes a lot of sense. That’s mental!’ And he says, ‘Well I didn’t really know him that well to be honest, but he was me da… anyway, what was that song you were playing?’ So we sort of left it at that.

“But we hung out a lot and we’d go looking at record stores together, it was like he became me sort of buddy outside of the (Commitments entourage), and Jeff was a bit of a hippy as well. And I guess within the cast, me and a couple of others were considered just a little bit different than the rest of them. I wasn’t on the razz every night. And everyone kind of lost the head a bit to be honest, friends of mine, I could see the old ego leave the body a bit because we were being treated as stars. And obviously when you treat someone like a star after a while they get a bit of an attitude, and I saw it in myself too and I didn’t like it.”

Hansard finally decided he’d had enough of The Commitments treadmill when the film people began to disappear and were replaced by a new management structure encouraging the cast to become a legitimate band. The last straw was when they were booked to play Bette Midler’s birthday party.

Glen: “I said, ‘Look, I’ve done me bit, man. Bette Midler’s birthday party, y’know, c’mon. I’ve a gig’. I went and played the first Clifden Blues Festival gig with The Frames the same night The Commitments were in LA playing for Bette Midler.”

I first saw The Frames a few months later in McGonagles, mid-January 1991, the night the US began bombing Iraq in the first Gulf War. Glen, with typical audacity, announced, “If this is the end of the world, we’re the last band you’ll ever see!” At this stage the ensemble still hadn’t quite merged the acoustic elements with the technoflash of the rhythm section, but they were fast developing into a ferociously tight band. And like everyone else, I was struck by Hansard’s obvious magnetism.

I caught them another three or four times that spring in the Baggot Inn, each successive show building in confidence and intensity. Plus, they looked great – The Bash Street Kids as drawn by R. Crumb.

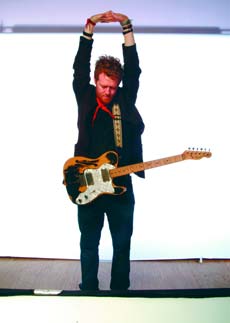

Under Noreen’s tutelage, Glen was now mascara-eyed and Bolan-esque, seething with anger and melancholy, jabbing holes in the Baggot ceiling with his brand new Rickenbacker and mock stabbing himself in the heart during ‘Before You Go’. Highlights of the early set included a mesmeric cover of the Velvets’ ‘Here She Comes Now’, the lustful angst of ‘Sleep With Me’ (I’m guessing the title here) – built around a couple of lines stolen from Loudon Wainwright – and the whiplash dynamics of ‘You Were Wrong’ and ‘The Dancer’.

At the time it seemed like The Frames had it all: youth, attitude and buckets of record company fuck-you money. The reality was somewhat different. For one, Glen was still the only member signed to Island, and the sessions for their debut album would be riddled with misunderstandings. Also, the band became the target of a certain amount of hometown derision. The post raggle-taggle fall-out had started to happen in the wake of Mike Scott’s effective disbanding of The Waterboys and moving to New York, and the breezy optimism of the late ’80s now began to look like woolly-headed naiveté in light of the upsurge of rap and Sub Pop.

Glen: “It’s funny that you should say we seemed so confident, because at the time our peers were Engine Alley and The Pale, and I remember thinking that we weren’t as good as either of those two bands. I think we were probably radically uncool because we were buskers. We were no Big Geraniums now, I’ve gotta tell ya, we didn’t go that far, but the bands that were around us seemed to have this incredible almost journalistic intelligence in their music, y’know, and it’s something I’ve always fought against in what I do. I never wanna get involved with that journalistic concept which means the Beach Boys are genius, that The Beatles are the best band that ever existed, therefore no-one will ever come along and top them. All our reviews said we were a bunch of hippies, and we were coming out of a time when the Hothouse Flowers had just started to not be a big, big band, and The Sawdoctors were popular, and there was this kind of naffness to an acoustic guitar and a fiddle.”

Colm: “I think at that time as well there was a classic lack of communication between bands, that was the order of the day; basically you’d scowl at each other across a room…”

Glen: “… but we didn’t scowl and that was the thing that kind of set us apart. We were like, ‘Howya!’ There was a couple of strange times, like meeting the Sultans Of Ping for instance, I remember meeting them and they were just so full of themselves, they were just like, ‘Who the fuck are the Frames? Fuck off.’ I mean, I couldn’t deal with it, and they were like, ‘Johnny fuckin’ Outspan’, accusing me of using the film to sort of… the thing was, I had to try and point out to everyone: ‘I was in this band before this fucking film happened!’ I know it sorta sounds stupid but it’s why I cut me hair off, I wanted to be not recognised as Outspan Foster, I wanted to be recognised as yer man Glen out of The Frames.”